P-values and confidence intervals

On this page

📊 Statistical Precision: The Evidence Architecture

You'll master the twin pillars that transform raw data into clinical decisions: p-values reveal whether observed effects are likely real or mere chance, while confidence intervals define the plausible range and magnitude of those effects. Together, they form your evidence architecture for interpreting studies, distinguishing statistical noise from genuine signals, and determining whether findings matter enough to change practice. This lesson builds your fluency in reading the statistical language that underpins every treatment guideline, diagnostic test, and therapeutic choice you'll make.

📌 Remember: PANIC for P-value interpretation - Probability of observing data, Assuming null hypothesis true, Not probability null is true, Influenced by sample size, Cannot prove causation

Statistical Foundation Architecture

The statistical evidence hierarchy operates through interconnected probability frameworks:

- P-values (α = 0.05 standard)

- Probability of observing data assuming null hypothesis true

- Type I error rate: 5% false positive threshold

- Medical research standard: p < 0.05

- High-stakes decisions: p < 0.01 or p < 0.001

- Bonferroni correction: α/n for multiple comparisons

- Confidence Intervals (95% standard)

- Range containing true parameter with 95% probability

- Width inversely related to sample size and precision

- Narrow CI: High precision, large sample

- Wide CI: Low precision, small sample

- Margin of error = Critical value × Standard error

⭐ Clinical Pearl: A 95% CI that excludes the null value corresponds to p < 0.05 in two-tailed testing. When CI includes null value, p > 0.05 indicates insufficient evidence against null hypothesis.

| Statistical Measure | Threshold | Clinical Interpretation | Sample Size Impact | Error Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-value | < 0.05 | Statistically significant | Smaller p with larger n | Type I (α) |

| 95% CI | Excludes null | Clinically meaningful range | Narrower with larger n | Type II (β) |

| 99% CI | Wider range | Higher confidence level | 2.6× wider than 95% | Reduced Type I |

| Power | ≥ 80% | Adequate sample size | Increases with larger n | Type II (1-β) |

| Effect size | Cohen's d > 0.5 | Moderate clinical impact | Independent of sample size | Clinical significance |

The precision of statistical inference depends on sample size (n), effect size (δ), and variability (σ). Standard error decreases proportionally to √n, making larger studies exponentially more precise. Power analysis requires α = 0.05, β = 0.20 (80% power), effect size estimation, and population variance to determine adequate sample size.

Connect these statistical foundations through hypothesis testing frameworks to understand how p-values and confidence intervals work together in clinical decision-making.

📊 Statistical Precision: The Evidence Architecture

🎯 Hypothesis Testing: The Clinical Decision Engine

📌 Remember: HATS for Hypothesis Testing - H₀ assumes no difference, Alternative claims difference exists, Type I rejects true null, Statistical power detects true alternatives

Decision Framework Architecture

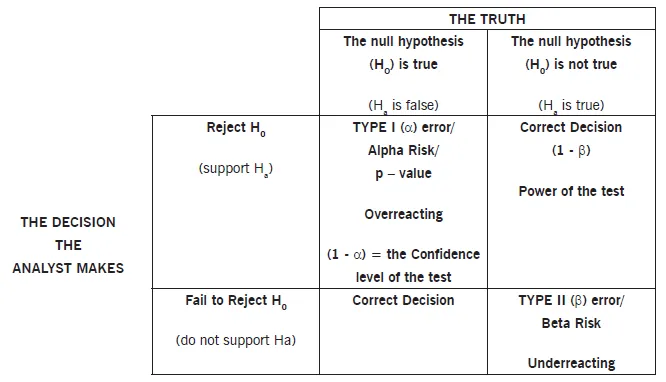

The hypothesis testing machinery operates through systematic error control:

- Null Hypothesis (H₀): No difference or no effect

- Default assumption requiring evidence to overturn

- Conservative approach: Maintains status quo until proven otherwise

- Drug trials: New treatment = Standard treatment

- Diagnostic tests: Test accuracy = Chance level

- Risk factors: Exposure = No increased risk

- Alternative Hypothesis (H₁): Difference exists or effect present

- Research hypothesis requiring statistical evidence

- Directional claims supported by data analysis

- Two-tailed: μ₁ ≠ μ₂ (difference in either direction)

- One-tailed: μ₁ > μ₂ or μ₁ < μ₂ (specific direction)

⭐ Clinical Pearl: Type I error (α) represents false positive rate - concluding treatment works when it doesn't. Type II error (β) represents false negative rate - missing real treatment effects. Power = 1-β measures ability to detect true effects.

| Error Type | Definition | Clinical Consequence | Control Method | Typical Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I (α) | False Positive | Adopt ineffective treatment | Set α level | 5% |

| Type II (β) | False Negative | Miss effective treatment | Increase sample size | 20% |

| Power (1-β) | True Positive | Detect real effects | Adequate sample size | 80% |

| Specificity | True Negative | Correctly reject null | Proper study design | 95% |

| Sensitivity | True Positive | Detect true alternatives | Sufficient power | 80% |

Statistical power depends on four interconnected factors: effect size (larger effects easier to detect), sample size (more data increases power), significance level (lower α reduces power), and population variability (less noise increases power). Power analysis calculates required sample size to achieve 80% power for detecting clinically meaningful differences at α = 0.05.

Connect hypothesis testing logic through p-value interpretation principles to understand how probability calculations support clinical decision-making.

🎯 Hypothesis Testing: The Clinical Decision Engine

🔍 P-Value Mastery: The Probability Decoder

📌 Remember: PROVE for P-value interpretation - Probability of data given H₀, Random sampling assumption, One-time calculation, Varies with sample size, Evidence strength not effect size

Probability Calculation Framework

P-values represent conditional probabilities calculated under specific statistical assumptions:

- P-value Definition: P(Data | H₀ true)

- Probability of observing current data or more extreme

- Assumes null hypothesis is true throughout calculation

- NOT probability that null hypothesis is true

- NOT probability of replication in future studies

- NOT measure of clinical importance or effect size

- Calculation Process: Test statistic → Probability distribution → P-value

- Z-test: Standard normal distribution for large samples

- T-test: Student's t-distribution for small samples (n < 30)

- Degrees of freedom = n-1 for one-sample tests

- Degrees of freedom = n₁+n₂-2 for two-sample tests

⭐ Clinical Pearl: P-values decrease with larger sample sizes even for identical effect sizes. A clinically trivial difference can achieve p < 0.001 with sufficient sample size, while clinically important differences may show p > 0.05 in underpowered studies.

| P-value Range | Evidence Strength | Clinical Interpretation | Replication Probability | Decision Framework |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p < 0.001 | Very Strong | Highly unlikely under H₀ | >95% replication | Strong evidence against H₀ |

| p < 0.01 | Strong | Unlikely under H₀ | >90% replication | Good evidence against H₀ |

| p < 0.05 | Moderate | Somewhat unlikely under H₀ | >80% replication | Sufficient evidence against H₀ |

| p = 0.05-0.10 | Weak | Borderline evidence | 50-80% replication | Insufficient evidence |

| p > 0.10 | None | Consistent with H₀ | <50% replication | No evidence against H₀ |

Common p-value misconceptions include: P(H₀|Data) confusion (Bayesian posterior probability), replication probability misinterpretation, effect size conflation, and clinical significance assumption. P-values measure evidence strength against null hypothesis under frequentist probability framework, not probability of hypotheses or clinical importance.

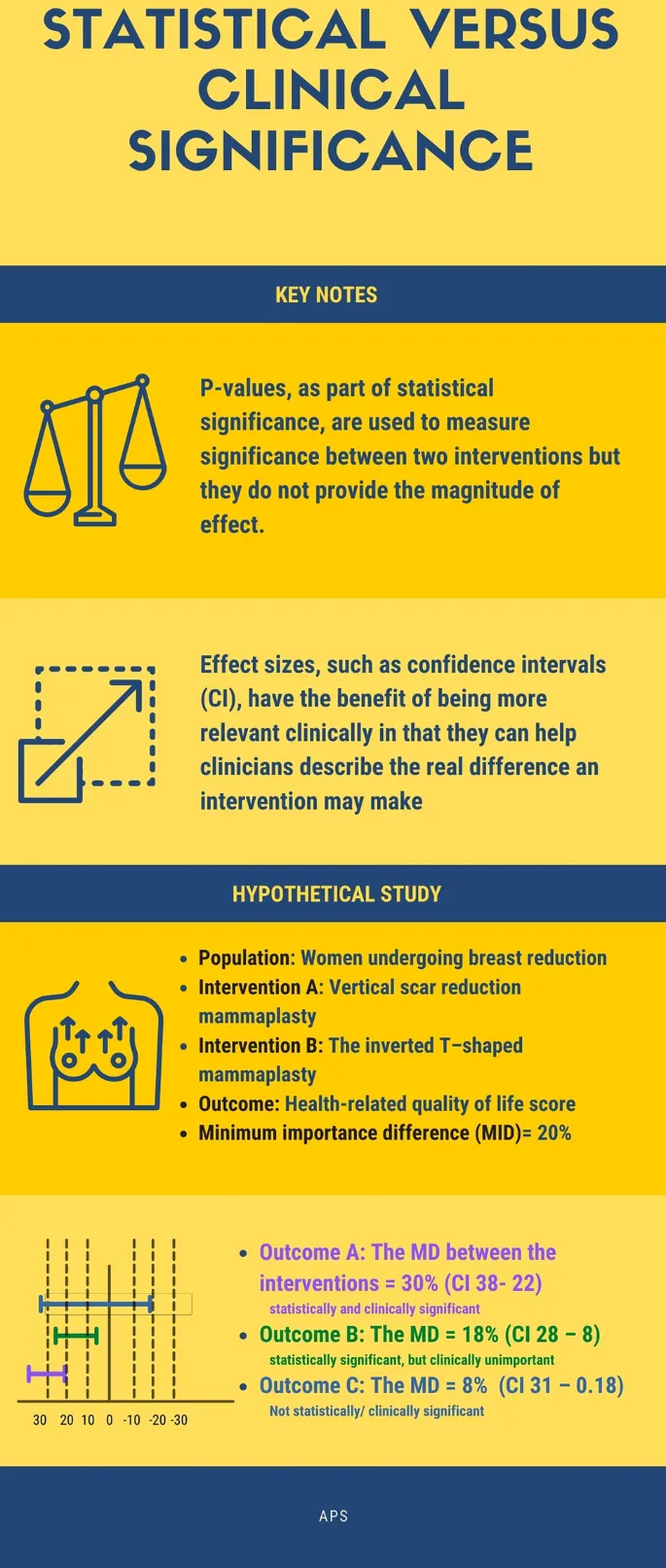

Sample size effects create p-value paradoxes: underpowered studies miss clinically important effects (Type II errors), while overpowered studies detect clinically trivial differences (statistical significance without clinical relevance). Effect size measures (Cohen's d, odds ratios, mean differences) provide clinical magnitude independent of sample size.

Connect p-value interpretation through confidence interval construction to understand how range estimates complement point probability calculations.

🔍 P-Value Mastery: The Probability Decoder

📏 Confidence Intervals: The Precision Boundary System

📌 Remember: CRIME for CI interpretation - Contains true parameter 95% of time, Range of plausible values, Inverse relationship with sample size, Margin of error calculation, Excludes null means significant

Interval Construction Architecture

Confidence interval construction follows mathematical precision with clinical interpretation:

- 95% Confidence Interval: Point Estimate ± Margin of Error

- Margin of Error = Critical Value × Standard Error

- Standard Error decreases with √n (square root of sample size)

- Larger samples → Smaller standard errors → Narrower intervals

- Higher confidence levels → Larger critical values → Wider intervals

- Greater variability → Larger standard errors → Wider intervals

- Critical Values depend on distribution and confidence level:

- Z-distribution: ±1.96 for 95% CI, ±2.58 for 99% CI

- T-distribution: Varies by degrees of freedom (larger for smaller samples)

⭐ Clinical Pearl: 95% CI means if we repeated the study 100 times, approximately 95 intervals would contain the true parameter value. The specific interval from our study either contains the true value (probability = 1) or doesn't (probability = 0).

| Parameter Type | Formula | Critical Value | Interpretation | Clinical Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (large n) | x̄ ± 1.96(σ/√n) | Z = 1.96 | Average value range | Blood pressure, lab values |

| Mean (small n) | x̄ ± t(s/√n) | t varies by df | Average with uncertainty | Small clinical trials |

| Proportion | p̂ ± 1.96√(p̂q̂/n) | Z = 1.96 | Percentage range | Disease prevalence, cure rates |

| Difference | (x̄₁-x̄₂) ± t(SE) | t varies by df | Treatment effect range | Drug efficacy comparisons |

| Odds Ratio | exp(ln(OR) ± 1.96×SE) | Z = 1.96 | Risk ratio range | Case-control studies |

Confidence level interpretation: 95% confidence refers to the long-run frequency of intervals containing true parameters, not the probability that our specific interval contains the true value. Higher confidence levels (99%) create wider intervals with greater certainty of capturing true parameters.

Relationship to hypothesis testing: When 95% CI excludes null value, p < 0.05 for two-tailed test. When 95% CI includes null value, p > 0.05 indicates insufficient evidence. CI width provides precision information that p-values cannot convey.

Connect confidence interval precision through clinical significance assessment to understand how statistical ranges translate into meaningful medical decisions.

📏 Confidence Intervals: The Precision Boundary System

⚖️ Clinical Significance: The Medical Relevance Filter

📌 Remember: SCALE for Clinical Significance - Size of effect matters, Cost-benefit analysis, Applicability to patients, Long-term outcomes, Ethical considerations

Medical Relevance Framework

Clinical significance evaluation requires multi-dimensional assessment beyond statistical calculations:

- Effect Size Measures quantify practical importance:

- Cohen's d: Standardized mean difference (0.2 small, 0.5 medium, 0.8 large)

- Number Needed to Treat (NNT): 1/Absolute Risk Reduction

- NNT = 2-5: Highly effective interventions

- NNT = 6-10: Moderately effective interventions

- NNT > 20: Questionable clinical value

- Minimal Clinically Important Difference (MCID): Patient-perceived benefit

- Clinical Context Factors:

- Baseline risk of patient population

- Alternative treatment options and comparative effectiveness

- Adverse effects and risk-benefit ratio

- Cost-effectiveness and resource allocation

⭐ Clinical Pearl: Large studies can detect statistically significant but clinically trivial differences. Small studies may miss clinically important but statistically non-significant effects. Effect size and confidence intervals provide better clinical guidance than p-values alone.

| Scenario | Statistical Result | Effect Size | Clinical Interpretation | Clinical Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large RCT | p < 0.001 | Small (d = 0.1) | Statistically significant, clinically trivial | Do not implement |

| Small RCT | p = 0.12 | Large (d = 0.9) | Not significant, clinically important | Consider larger study |

| Meta-analysis | p < 0.05 | Medium (d = 0.5) | Significant and meaningful | Implement with monitoring |

| Pilot study | p = 0.08 | Very large (d = 1.2) | Borderline significance, major effect | Proceed to full trial |

| Registry study | p < 0.0001 | Trivial (d = 0.05) | Highly significant, no clinical value | Academic interest only |

Minimal Clinically Important Differences vary by condition and outcome measure: Pain scales (1-2 points on 10-point scale), Quality of life (0.5 standard deviations), Blood pressure (5-10 mmHg for cardiovascular outcomes), HbA1c (0.5% for diabetes management). Patient-reported outcomes often define clinical relevance better than biomarker changes.

Cost-effectiveness analysis integrates clinical benefits with economic considerations: Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALYs), Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratios (ICERs), and budget impact determine healthcare implementation decisions beyond statistical significance.

Connect clinical significance assessment through systematic integration frameworks to understand how multiple statistical and clinical factors combine in evidence-based medicine.

⚖️ Clinical Significance: The Medical Relevance Filter

🔗 Evidence Integration: The Multi-Dimensional Assessment Matrix

📌 Remember: MERGE for Evidence Integration - Meta-analysis synthesis, Effect size consistency, Risk of bias assessment, GRADE quality rating, External validity evaluation

Multi-Dimensional Assessment Architecture

Evidence synthesis requires systematic evaluation across multiple quality dimensions:

- Statistical Synthesis Methods:

- Fixed-effects models: Assume single true effect across studies

- Random-effects models: Allow effect variation between studies

- I² statistic: 0-25% low heterogeneity, 50-75% moderate, >75% high

- Tau²: Between-study variance in random-effects models

- Q-statistic: Chi-square test for heterogeneity (p < 0.10 suggests heterogeneity)

- Publication Bias Assessment:

- Funnel plot asymmetry: Visual inspection for missing studies

- Egger's test: Statistical test for small-study effects (p < 0.05 suggests bias)

- Trim-and-fill method: Imputes missing studies and adjusts effect estimates

⭐ Clinical Pearl: High heterogeneity (I² > 75%) suggests important differences between studies in populations, interventions, or outcomes. Subgroup analysis and meta-regression can explore sources of heterogeneity and identify patient-specific effects.

| Evidence Component | Assessment Method | Quality Indicators | Clinical Impact | Decision Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Power | Sample size calculation | >80% power | Adequate effect detection | High |

| Risk of Bias | Cochrane RoB tool | Low risk domains | Internal validity | Very High |

| Heterogeneity | I² and Tau² | <50% I² | Consistency across studies | High |

| Publication Bias | Funnel plots, Egger's | Symmetric distribution | Complete evidence base | Moderate |

| External Validity | PICO assessment | Representative populations | Generalizability | High |

Network meta-analysis enables indirect comparisons between treatments never directly compared, using transitivity assumptions and consistency evaluation. Surface Under Cumulative Ranking (SUCRA) provides probabilistic rankings of treatment effectiveness across multiple interventions.

Real-world evidence integration combines randomized trial efficacy with observational study effectiveness, registry data, and electronic health records to assess pragmatic treatment effects in diverse patient populations with complex comorbidities.

Connect evidence integration through rapid clinical reference tools to transform comprehensive assessments into practical decision-making frameworks.

🔗 Evidence Integration: The Multi-Dimensional Assessment Matrix

🎯 Clinical Decision Mastery: The Rapid Assessment Toolkit

📌 Remember: RAPID for Clinical Decisions - Risk stratification, Assess pre-test probability, Post-test probability calculation, Integrate patient factors, Decision with uncertainty quantification

Essential Clinical Arsenal

Statistical Thresholds for Immediate Application:

-

P-value Interpretation Hierarchy:

- p < 0.001: Overwhelming evidence - implement immediately

- p < 0.01: Strong evidence - adopt with monitoring

- p < 0.05: Moderate evidence - consider patient factors

- p = 0.05-0.10: Weak evidence - individualize decisions

- p > 0.10: Insufficient evidence - maintain current practice

-

Confidence Interval Clinical Rules:

- Narrow CI excluding null: High precision, strong evidence

- Wide CI excluding null: Low precision, uncertain magnitude

- CI including null: Insufficient evidence regardless of width

- CI width > 2× MCID: Clinically uninformative precision

⭐ Clinical Pearl: Number Needed to Treat (NNT) provides immediate clinical relevance: NNT = 2 means 1 in 2 patients benefit, NNT = 10 means 1 in 10 patients benefit. NNT confidence intervals quantify uncertainty in treatment effectiveness.

| Clinical Scenario | Statistical Evidence | Decision Framework | Action Threshold | Monitoring Plan |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life-threatening | p < 0.05, NNT < 10 | Immediate implementation | >50% benefit probability | Intensive monitoring |

| Chronic disease | p < 0.01, NNT < 20 | Gradual implementation | >70% benefit probability | Regular assessment |

| Preventive care | p < 0.001, NNT < 50 | Population-based | >80% benefit probability | Long-term tracking |

| Experimental | p < 0.05, wide CI | Research setting | >60% benefit probability | Continuous evaluation |

| Cost-intensive | p < 0.01, ICER favorable | Economic evaluation | Cost-effective threshold | Budget impact analysis |

Rapid Evidence Assessment Protocol: Study design hierarchy (RCT > cohort > case-control), sample size adequacy (power >80%), effect size magnitude (Cohen's d >0.5), confidence interval precision (excludes null), clinical applicability (similar population), and cost-effectiveness (acceptable ICER).

Clinical Uncertainty Management: Shared decision-making when evidence quality moderate, patient preference integration for value-sensitive decisions, trial of therapy for uncertain diagnoses, and safety-netting for low-probability serious conditions.

Understanding p-values and confidence intervals provides the statistical foundation for evidence-based medicine, enabling precise interpretation of research findings and confident clinical decision-making in complex patient care scenarios.

🎯 Clinical Decision Mastery: The Rapid Assessment Toolkit

Practice Questions: P-values and confidence intervals

Test your understanding with these related questions

A scientist in Chicago is studying a new blood test to detect Ab to EBV with increased sensitivity and specificity. So far, her best attempt at creating such an exam reached 82% sensitivity and 88% specificity. She is hoping to increase these numbers by at least 2 percent for each value. After several years of work, she believes that she has actually managed to reach a sensitivity and specificity much greater than what she had originally hoped for. She travels to China to begin testing her newest blood test. She finds 2,000 patients who are willing to participate in her study. Of the 2,000 patients, 1,200 of them are known to be infected with EBV. The scientist tests these 1,200 patients' blood and finds that only 120 of them tested negative with her new exam. Of the patients who are known to be EBV-free, only 20 of them tested positive. Given these results, which of the following correlates with the exam's specificity?