Ethics/Biostatistics

On this page

📊 Statistical Foundation Mastery: The Numbers That Drive Medicine

Medical decisions rest on two pillars: doing what's right and knowing what's true. This lesson equips you to navigate both-mastering the ethical frameworks that guide patient care and the statistical tools that transform raw data into reliable evidence. You'll learn to recognize distribution patterns in clinical datasets, select appropriate tests for different research questions, quantify uncertainty with precision, and integrate these skills into the critical thinking physicians use daily. By connecting moral reasoning with mathematical rigor, you'll build the foundation for evidence-based practice that honors both science and humanity.

Central Tendency: The Heart of Your Data

Central tendency measures reveal the "typical" value in medical datasets, but each measure tells a different clinical story:

-

Mean (Arithmetic Average)

- Most sensitive to extreme values (outliers)

- Best for: normally distributed continuous data

- Clinical use: laboratory reference ranges, drug dosing calculations

- Formula: $\bar{x} = \frac{\sum x_i}{n}$

-

Median (Middle Value)

- Resistant to outliers and skewed distributions

- Best for: non-normal data, ordinal scales

- Clinical use: hospital length of stay, pain scores

- Position: 50th percentile of ordered data

-

Mode (Most Frequent Value)

- Only measure applicable to categorical data

- Best for: nominal variables, discrete counts

- Clinical use: most common diagnosis, preferred treatment choice

📌 Remember: MOM - Mean for normal distributions, Outlier-resistant median for skewed data, Mode for categories. Mean pulls toward outliers, median stays centered, mode shows peaks.

Dispersion Measures: Quantifying Clinical Variability

Dispersion measures reveal how spread out your data points are, critical for understanding treatment consistency and population heterogeneity:

| Measure | Formula | Outlier Sensitivity | Best Use | Clinical Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | Max - Min | Extremely high | Quick assessment | Blood pressure readings |

| Interquartile Range | Q3 - Q1 | Low | Skewed data | Hospital costs |

| Variance | $s^2 = \frac{\sum(x_i - \bar{x})^2}{n-1}$ | High | Theoretical work | Research calculations |

| Standard Deviation | $s = \sqrt{s^2}$ | High | Normal distributions | Lab reference ranges |

| Coefficient of Variation | $CV = \frac{s}{\bar{x}} \times 100%$ | Moderate | Comparing variability | Drug concentration studies |

Understanding dispersion patterns reveals critical clinical insights about treatment reliability and patient population characteristics.

📊 Statistical Foundation Mastery: The Numbers That Drive Medicine

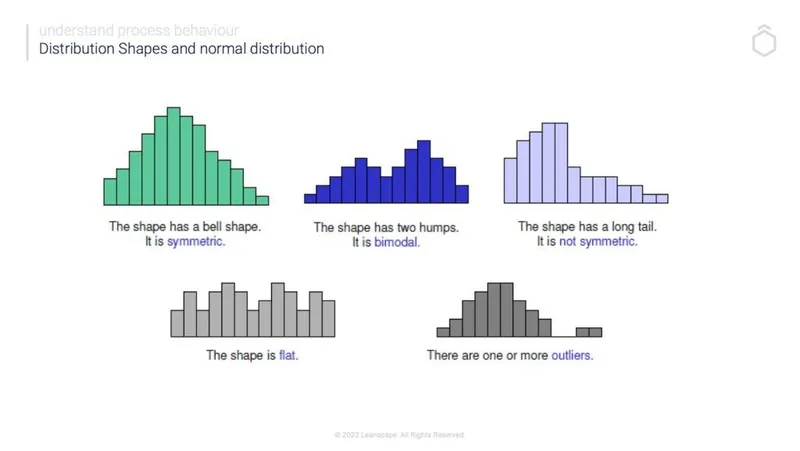

🎯 Distribution Architecture: The Shape of Medical Reality

Normal Distribution: The Statistical Gold Standard

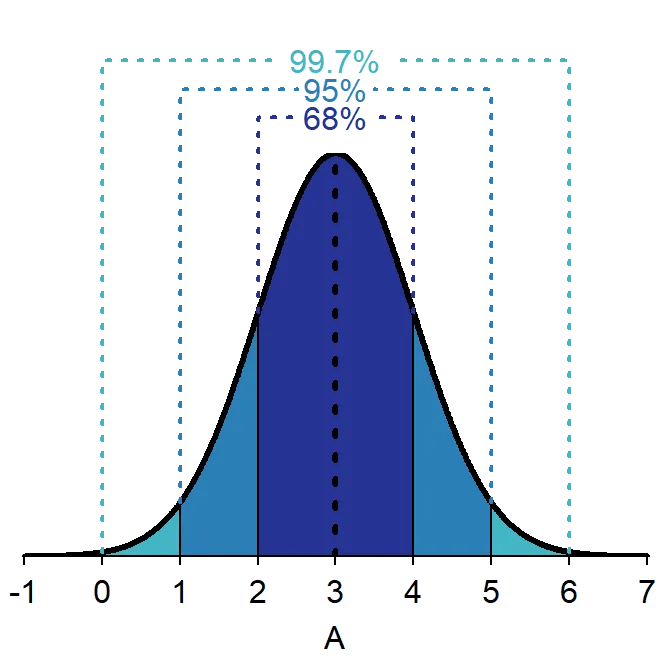

The normal distribution (Gaussian curve) represents the foundation of parametric statistics, characterized by:

- Perfect symmetry around the mean

- Bell-shaped curve with single peak

- Mean = Median = Mode (all central measures identical)

- 68-95-99.7 rule for standard deviation intervals

- Asymptotic tails approaching but never touching zero

💡 Master This: Normal distributions enable powerful parametric tests (t-tests, ANOVA, regression) that provide maximum statistical power. When data follows normal patterns, you can make precise probability statements about individual values and population parameters.

Clinical Examples of Normal Distributions:

- Adult height and weight measurements

- Blood pressure in healthy populations

- Many laboratory values (hemoglobin, cholesterol)

- IQ scores and cognitive assessments

- Drug plasma concentrations at steady state

Skewed Distributions: When Reality Bends the Curve

Skewed distributions occur frequently in medical data, requiring different analytical approaches:

Right-Skewed (Positive Skew):

- Tail extends toward higher values

- Mean > Median > Mode

- Common in medical data due to biological constraints

- Examples: hospital length of stay, healthcare costs, reaction times

- Analysis: Use median and IQR; consider log transformation

Left-Skewed (Negative Skew):

- Tail extends toward lower values

- Mode > Median > Mean

- Less common in medical settings

- Examples: age at death in developed countries, test scores with ceiling effects

- Analysis: Use median and IQR; consider reflection then log transformation

📌 Remember: TAIL tells the TALE - Skewness direction follows the tail. Right skew = positive skew = tail points right. Left skew = negative skew = tail points left. The mean always chases the tail.

Bimodal and Multimodal Patterns

Multiple peaks in distributions often reveal clinically significant subpopulations:

- Bimodal: Two distinct peaks suggesting two populations

- Multimodal: Multiple peaks indicating several subgroups

- Clinical significance: May indicate different disease phenotypes, treatment responders vs. non-responders, or demographic subgroups

Recognition Strategy:

- Look for multiple peaks in histograms

- Check for plateau regions between peaks

- Consider mixture models for analysis

- Investigate clinical subgroups that might explain patterns

⭐ Clinical Pearl: Bimodal distributions in treatment response data often indicate responder vs. non-responder populations. This pattern suggests the need for personalized medicine approaches or biomarker-guided therapy selection.

Distribution recognition connects directly to appropriate statistical test selection and clinical interpretation frameworks.

🎯 Distribution Architecture: The Shape of Medical Reality

📐 Variability Quantification: Measuring Clinical Precision

Standard Deviation: The Clinical Workhorse

Standard deviation quantifies average distance from the mean, providing the foundation for most clinical reference ranges and statistical tests:

Calculation Process:

- Calculate mean: $\bar{x} = \frac{\sum x_i}{n}$

- Find deviations: $(x_i - \bar{x})$ for each value

- Square deviations: $(x_i - \bar{x})^2$

- Sum squared deviations: $\sum(x_i - \bar{x})^2$

- Divide by (n-1): $s^2 = \frac{\sum(x_i - \bar{x})^2}{n-1}$

- Take square root: $s = \sqrt{s^2}$

💡 Master This: Standard deviation shares the same units as your original data, making it clinically interpretable. A hemoglobin SD of 1.2 g/dL means typical values vary by ±1.2 g/dL from the average, directly applicable to clinical decision-making.

Clinical Applications:

- Laboratory reference ranges: Mean ± 2 SD captures 95% of healthy population

- Quality control: Values beyond 3 SD trigger investigation

- Treatment monitoring: Changes >2 SD suggest real clinical change

- Research power: Smaller SD increases ability to detect treatment effects

Coefficient of Variation: Standardized Comparison Tool

The coefficient of variation (CV) enables comparison of variability across different scales and units:

$$CV = \frac{\text{Standard Deviation}}{\text{Mean}} \times 100%$$

Interpretation Guidelines:

- CV < 10%: Low variability, high precision

- CV 10-20%: Moderate variability, acceptable precision

- CV 20-30%: High variability, concerning precision

- CV > 30%: Very high variability, poor precision

| Laboratory Test | Typical CV | Clinical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Glucose | 3-5% | Excellent precision |

| Cholesterol | 2-4% | Excellent precision |

| Creatinine | 4-8% | Good precision |

| Troponin | 8-15% | Acceptable precision |

| PSA | 15-25% | Moderate precision |

Robust Measures: Outlier-Resistant Alternatives

When data contains outliers or follows non-normal distributions, robust measures provide more reliable variability assessment:

Interquartile Range (IQR):

- Definition: Q3 - Q1 (75th percentile - 25th percentile)

- Advantage: Unaffected by extreme values

- Clinical use: Skewed data like hospital costs, length of stay

- Outlier detection: Values beyond Q1 - 1.5×IQR or Q3 + 1.5×IQR

Median Absolute Deviation (MAD):

- Definition: Median of absolute deviations from median

- Advantage: Extremely robust to outliers

- Clinical use: When extreme outliers present

- Calculation: MAD = median(|xi - median(x)|)

⭐ Clinical Pearl: IQR captures the middle 50% of your data, providing outlier-resistant spread measurement. In skewed medical data (costs, length of stay), IQR often provides more clinically meaningful variability assessment than standard deviation.

Robust measures ensure accurate variability assessment even when data violates normal distribution assumptions.

📐 Variability Quantification: Measuring Clinical Precision

🔍 Pattern Recognition Mastery: Identifying Distribution Signatures

Visual Pattern Recognition Framework

Step 1: Overall Shape Assessment

- Symmetrical: Consider normal distribution

- Single tail extension: Identify skew direction

- Multiple peaks: Look for bimodal/multimodal patterns

- Flat appearance: Suspect uniform distribution

- Extreme outliers: Consider contaminated normal

Step 2: Central Tendency Relationships

- Mean ≈ Median ≈ Mode: Strong normal distribution evidence

- Mean > Median: Right skew pattern

- Mean < Median: Left skew pattern

- Multiple modes: Multimodal distribution confirmed

Step 3: Tail Behavior Analysis

- Symmetric tails: Normal or other symmetric distributions

- Heavy tails: Consider t-distribution or contaminated normal

- Light tails: Possible uniform or truncated distribution

- Asymmetric tails: Confirms skewness direction

💡 Master This: The Mean-Median relationship provides the fastest distribution assessment. In right-skewed data, extreme high values pull the mean above the median. In left-skewed data, extreme low values pull the mean below the median.

Statistical Tests for Normality

Shapiro-Wilk Test:

- Best for: Small samples (n < 50)

- Null hypothesis: Data follows normal distribution

- Interpretation: p < 0.05 suggests non-normality

- Advantage: Most powerful normality test for small samples

Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test:

- Best for: Large samples (n > 50)

- Null hypothesis: Data follows specified distribution

- Interpretation: p < 0.05 suggests distribution mismatch

- Advantage: Can test against any specified distribution

Anderson-Darling Test:

- Best for: Moderate samples (n = 20-100)

- Null hypothesis: Data follows normal distribution

- Interpretation: p < 0.05 suggests non-normality

- Advantage: More sensitive to tail deviations

| Sample Size | Recommended Test | Critical p-value | Action if p < 0.05 |

|---|---|---|---|

| n < 20 | Visual inspection | N/A | Use non-parametric tests |

| n = 20-50 | Shapiro-Wilk | 0.05 | Consider transformation |

| n = 50-100 | Anderson-Darling | 0.05 | Use robust methods |

| n > 100 | Kolmogorov-Smirnov | 0.05 | Apply CLT principles |

Clinical Context Pattern Recognition

Biological Constraint Patterns:

- Floor effects: Minimum possible values (reaction times, survival times)

- Ceiling effects: Maximum possible values (test scores, age at death)

- Natural boundaries: Physical limits creating skewness

Population Mixture Patterns:

- Bimodal age distributions: Pediatric vs. adult populations

- Treatment response patterns: Responders vs. non-responders

- Disease severity patterns: Mild vs. severe phenotypes

Measurement Artifact Patterns:

- Digit preference: Rounding to preferred numbers (0, 5)

- Detection limits: Laboratory assay thresholds

- Reporting bias: Selective outcome reporting

⭐ Clinical Pearl: Bimodal distributions in clinical data often indicate two distinct populations that should be analyzed separately. This pattern frequently reveals important clinical subgroups requiring different treatment approaches.

Pattern recognition skills directly translate to appropriate statistical test selection and meaningful clinical interpretation.

🔍 Pattern Recognition Mastery: Identifying Distribution Signatures

⚖️ Statistical Test Selection: Matching Methods to Data Reality

Parametric Test Requirements

Fundamental Assumptions:

- Normality: Data follows normal distribution

- Independence: Observations unrelated to each other

- Homoscedasticity: Equal variances across groups

- Linearity: Relationships follow straight-line patterns (regression)

When Assumptions Met:

- Maximum statistical power to detect differences

- Precise confidence intervals and p-values

- Robust to minor assumption violations with adequate sample size

- Interpretable effect sizes with clinical meaning

Common Parametric Tests:

- One-sample t-test: Compare sample mean to known value

- Two-sample t-test: Compare means between two groups

- Paired t-test: Compare before/after measurements

- ANOVA: Compare means across multiple groups

- Linear regression: Model continuous outcome relationships

💡 Master This: Parametric tests provide maximum power when assumptions are met, but can produce misleading results when assumptions are violated. The trade-off between power and robustness drives test selection decisions.

Non-Parametric Alternatives

Key Advantages:

- Distribution-free: No normality assumptions required

- Robust to outliers: Extreme values don't distort results

- Applicable to ordinal data: Works with ranked measurements

- Fewer assumptions: More broadly applicable

Power Trade-offs:

- 80-95% efficiency compared to parametric tests when normality holds

- Superior performance when assumptions violated

- Broader applicability across data types and distributions

| Parametric Test | Non-Parametric Alternative | Use When |

|---|---|---|

| One-sample t-test | Wilcoxon signed-rank | Non-normal, small sample |

| Two-sample t-test | Mann-Whitney U | Skewed data, outliers |

| Paired t-test | Wilcoxon signed-rank | Non-normal differences |

| One-way ANOVA | Kruskal-Wallis | Non-normal, unequal variances |

| Pearson correlation | Spearman correlation | Non-linear relationships |

Sample Size Considerations

Small Samples (n < 30):

- Normality testing unreliable: Visual inspection preferred

- Non-parametric tests safer: Less assumption-dependent

- Exact tests available: Provide precise p-values

- Bootstrap methods: Generate empirical distributions

Large Samples (n > 100):

- Central Limit Theorem applies: Means approach normality

- Parametric tests robust: Minor assumption violations acceptable

- Asymptotic methods valid: Large-sample approximations accurate

- Effect size emphasis: Statistical significance easier to achieve

Moderate Samples (n = 30-100):

- Formal normality testing: Shapiro-Wilk, Anderson-Darling

- Assumption checking critical: Moderate power for detection

- Transformation options: Log, square root, Box-Cox

- Robust methods: Trimmed means, bootstrap confidence intervals

⭐ Clinical Pearl: With n > 100, the Central Limit Theorem ensures that sample means follow normal distributions even when individual observations don't. This enables parametric test use even with moderately skewed data.

Statistical test selection directly impacts the validity and interpretability of research findings and clinical conclusions.

⚖️ Statistical Test Selection: Matching Methods to Data Reality

🔗 Advanced Integration: Multi-Dimensional Statistical Landscapes

Measurement Scale Integration

Nominal-Ordinal-Interval-Ratio (NOIR) Framework:

Nominal Variables:

- Categories without order: Gender, blood type, diagnosis

- Statistical measures: Mode, frequencies, proportions

- Appropriate tests: Chi-square, Fisher's exact

- Clinical examples: Treatment response (yes/no), adverse events

Ordinal Variables:

- Ranked categories: Pain scales, disease severity, functional status

- Statistical measures: Median, percentiles, rank correlations

- Appropriate tests: Mann-Whitney, Kruskal-Wallis, Spearman correlation

- Clinical examples: NYHA class, tumor grade, patient satisfaction

Interval Variables:

- Equal intervals, arbitrary zero: Temperature (Celsius), standardized scores

- Statistical measures: Mean, standard deviation, Pearson correlation

- Appropriate tests: t-tests, ANOVA, linear regression

- Clinical examples: Blood pressure, laboratory values, age

Ratio Variables:

- Equal intervals, true zero: Height, weight, drug concentrations

- Statistical measures: All measures valid, geometric mean applicable

- Appropriate tests: All parametric and non-parametric tests

- Clinical examples: Biomarker levels, survival time, cost data

💡 Master This: Higher measurement scales include all properties of lower scales. Ratio data can be analyzed as interval, ordinal, or nominal, but information is lost with each step down. Choose the highest appropriate scale for maximum analytical power.

Mixed-Methods Statistical Approaches

Combining Continuous and Categorical Variables:

- ANCOVA: Continuous outcome, categorical groups, continuous covariates

- Logistic regression: Binary outcome, mixed predictor types

- Survival analysis: Time-to-event outcome, mixed predictors

- Mixed-effects models: Repeated measures with categorical and continuous factors

Multi-Scale Integration Strategies:

- Stratified analysis: Separate analyses within categorical subgroups

- Interaction testing: Formal tests of effect modification

- Propensity scoring: Balance groups on multiple confounders

- Machine learning: Pattern recognition across variable types

| Analysis Goal | Outcome Type | Predictor Types | Recommended Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group comparison | Continuous | Categorical + Continuous | ANCOVA |

| Risk prediction | Binary | Mixed | Logistic regression |

| Time-to-event | Survival | Mixed | Cox regression |

| Repeated measures | Continuous | Mixed + Time | Mixed-effects models |

| Pattern discovery | Any | Any | Machine learning |

Statistical vs. Clinical Significance Framework:

- Statistical significance: p < 0.05, confidence intervals exclude null

- Clinical significance: Meaningful difference for patient outcomes

- Effect size measures: Quantify practical importance

- Number needed to treat: Translate effects to clinical practice

Effect Size Interpretation Guidelines:

- Cohen's d: 0.2 small, 0.5 medium, 0.8 large effect

- Correlation (r): 0.1 small, 0.3 medium, 0.5 large association

- Odds ratio: 1.5 small, 2.5 medium, 4.0 large effect

- Number needed to treat: <10 excellent, 10-20 good, >20 modest benefit

📌 Remember: POWER-PRECISION-PRACTICE triangle - Statistical power detects differences, precision quantifies uncertainty, clinical practice determines relevance. All three dimensions must align for meaningful medical research.

Confidence Interval Integration:

- Width indicates precision: Narrow intervals suggest reliable estimates

- Clinical boundaries: Do intervals include clinically meaningful thresholds?

- Practical equivalence: Are confidence limits within equivalence margins?

- Decision-making: Do intervals support clear clinical recommendations?

⭐ Clinical Pearl: Large samples can detect statistically significant but clinically trivial differences. Always evaluate effect sizes and confidence intervals alongside p-values to determine practical importance for patient care.

Advanced integration skills enable comprehensive evaluation of complex medical research and support evidence-based clinical decision-making.

🔗 Advanced Integration: Multi-Dimensional Statistical Landscapes

🎯 Statistical Mastery Arsenal: Clinical Decision-Making Tools

Essential Statistical Thresholds

Critical Values for Clinical Practice:

- Significance level: α = 0.05 (5% Type I error rate)

- Power threshold: 80% minimum (β = 0.20, Type II error rate)

- Confidence level: 95% standard (99% for critical decisions)

- Effect size benchmarks: 0.2/0.5/0.8 for small/medium/large effects

- Sample size rule: n ≥ 30 for Central Limit Theorem application

Distribution Percentiles:

- 68% of data within ±1 standard deviation

- 95% of data within ±1.96 standard deviations

- 99.7% of data within ±3 standard deviations

- Outlier threshold: Beyond ±2 or ±3 standard deviations

- IQR outliers: Below Q1 - 1.5×IQR or above Q3 + 1.5×IQR

📌 Remember: 95-80-30 Rule - 95% confidence intervals, 80% minimum power, 30+ sample size for robust parametric analysis. These thresholds ensure reliable statistical inference in clinical research.

Rapid Assessment Framework

Data Type Decision Tree:

- Categorical data → Chi-square tests, Fisher's exact

- Ordinal data → Non-parametric rank tests

- Continuous normal → Parametric t-tests, ANOVA

- Continuous non-normal → Non-parametric alternatives

- Time-to-event → Survival analysis methods

Sample Size Quick Rules:

- n < 20: Use exact tests, avoid normality assumptions

- n = 20-30: Formal normality testing, consider transformations

- n = 30-100: Parametric tests if assumptions met

- n > 100: Central Limit Theorem enables parametric approaches

| Clinical Scenario | Statistical Approach | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Compare 2 groups | t-test or Mann-Whitney | Check normality, equal variances |

| Compare 3+ groups | ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis | Multiple comparisons, effect sizes |

| Before/after comparison | Paired t-test or Wilcoxon | Account for correlation |

| Categorical associations | Chi-square or Fisher's exact | Expected cell counts ≥5 |

| Correlation analysis | Pearson or Spearman | Linearity, outliers |

Clinical Interpretation Checklist: ✓ Statistical significance: Is p < 0.05? ✓ Clinical significance: Is effect size meaningful? ✓ Confidence intervals: Do they exclude clinically irrelevant values? ✓ Study design: Does methodology support causal inference? ✓ Generalizability: Does sample represent target population?

⭐ Clinical Pearl: Effect size often matters more than p-value for clinical decisions. A statistically significant finding with trivial effect size rarely justifies changing clinical practice, while a large effect size with marginal significance may warrant further investigation.

This statistical mastery arsenal enables confident evaluation of medical literature and supports evidence-based clinical practice through rigorous analytical thinking.

🎯 Statistical Mastery Arsenal: Clinical Decision-Making Tools

Practice Questions: Ethics/Biostatistics

Test your understanding with these related questions

A research team develops a new monoclonal antibody checkpoint inhibitor for advanced melanoma that has shown promise in animal studies as well as high efficacy and low toxicity in early phase human clinical trials. The research team would now like to compare this drug to existing standard of care immunotherapy for advanced melanoma. The research team decides to conduct a non-randomized study where the novel drug will be offered to patients who are deemed to be at risk for toxicity with the current standard of care immunotherapy, while patients without such risk factors will receive the standard treatment. Which of the following best describes the level of evidence that this study can offer?